In high school being labeled a Nerd was a term of detriment to ones social existence. It meant you read books on physics and chemistry and liked all those things which by high school definition was just naturally a repellent to girls. Now that I am older though i have to admit (with some chagrin) I am a nerd. No I am not trying to still Pharell and Hugo's demized spotlight (though they should of stuck with quasi-rap songs). No I am a RAP Nerd! I like Rakim (no homo), I like Nas (no homo), and i like Jean grey (though she wont return my calls. So now sadly i am way out of the loop, because way too many rap fans have stopped being Nerds and join the masses of mainstream rap jocks.

What are the signs you ask? Well the first sign of this change for the worse goes by the title G G G Gee Unit, and their absolute disregard for anything "real" when it comes to hip hop. Here are some examples.

1) they built their rep from shitting on a semirap/r&b singer who is 4 foot 2.

2) they all claim to be hardcore but blackchild stabbed 50 and is still breathing

3) 50 took out an order of protection on ja fucking rule

4) they all obviously reuse beats (with different instrumentation) and then rhymes using the same exact flow on them.

5) they got the balls to have a member who admits he hasn't rapped for more than a year but call's himself "the game"

6) they create a fake beef let the media hype it up (they were talking about it on CNN dammit) and then squash it in harlem (who from G-unit comes from Harlem? is Harlem a new niche market that G-unit has to find a wack rapper from?) to make up for the fact 50 has no street heaters on this album.

7) "If you go to radio/ we all know you fronting/"

all real "rap heads" need to go listen to Kool G Rap and Nas "fastlife" cause these g unit fools don't even know how to floss. talking bout candy shops and disco inferno those titles are weak and the songs are cornballish.

But this is just my opinion...........

__

R J Noriega

"Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one." - Charles Mackay

Saturday, March 26, 2005

B-MORE club music is coming down the WIRE

Da City Bass Line

Baltimore Club

Baltimore club, the ebullient and aggressive convolution of house and hip-hop that has germinated in Baltimore over the past fifteen years, is one of the city’s most unique and valuable musical manifestations. The sound is a deeply funky and eminently danceable style, developed in a scene of clubs, where DJs, producers, and dancers collide to create a bouncing and booming cross-cut rhythm unlike anything else coming out of the world’s urban sound systems. Although it is by Baltimorefor Baltimore, club is standing on the verge of national attention as much as anything our city has produced since John Waters. DJs in Philly, New York and L.A. are beginning to catch on and prowl B-more record stores for the tracks from our beloved cultural backwater.

The basic structure of quintessential Baltimore club boils down to several elements: a booming a-symmetrical bass, a quick chook-chooka-cha rhythm as distinctive as a Bo Diddley beat, and a sung or spoken “jingle” repeated and cut up into variations of increasing rhythmic complexity (called the sing-sing break or the think break).

Rod Lee, the revered master and one of the style’s originators, recently launched his own label, Club Kingz Records. His “ Let’s get HIGH ” track with K-Life, settles into a stroboscopic flicker on that single key word, “HIGH HIGH HIGH HIGH…” and feels like the summation of everything you’re on the dance floor to get.

Like the raw force of early rock, club is a propulsive, hilariously vulgar music for folks in need of release. “My music comes from anger,” Rod Lee told Stephen Janis in a recent interview in the local arts journal Link. “You got people going to the club to have a drink ’ cause they’re mad at their females. You got guys going to the club to get away from their bills … If you could sit there and make someone dance after they got divorced [laughter], I know I’m good!”

Non-club-going Baltimoreans have caught on to the sound listening to Friday night broadcasts on 92.3 FM. Some of the best DJs, including K-Swift, Frank Ski, and Cornbread are featured every week spinning at the most visible nightclub for the club sound, Club Choices on Charles Street. Rod Lee also has a regular Friday evening residency on the station.

Meanwhile, nationwide hipsters and tastemakers, like East Orange, New Jersey’s WFMU program director Brian Turner, have started ordering club tracks to add to their collections. While the original outlet for club, Music Liberated on West Saratoga, closed its doors after the death of proprietor Bernie Rabinowitz two years ago, and DJ Technic’s Club Tracks store just folded, Rod Lee plans to fill the gap this year with new shops on Monument Street and West Saratoga.

—Ian Nagoski

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Baltimore club music is the style which mr Swiss Beats is appropiating (aka biting) in order to make these new songs for cassidy ,T.I , Memphis Bleek, and Jae (Ness ate him) Millz. Its basically a looping style which use's Hip Hop phrases which would make good old uncle Luke blush. either way its party worthy and its not on MTV, so those in the know go give it a listen.

R J Noriega

Baltimore Club

Baltimore club, the ebullient and aggressive convolution of house and hip-hop that has germinated in Baltimore over the past fifteen years, is one of the city’s most unique and valuable musical manifestations. The sound is a deeply funky and eminently danceable style, developed in a scene of clubs, where DJs, producers, and dancers collide to create a bouncing and booming cross-cut rhythm unlike anything else coming out of the world’s urban sound systems. Although it is by Baltimorefor Baltimore, club is standing on the verge of national attention as much as anything our city has produced since John Waters. DJs in Philly, New York and L.A. are beginning to catch on and prowl B-more record stores for the tracks from our beloved cultural backwater.

The basic structure of quintessential Baltimore club boils down to several elements: a booming a-symmetrical bass, a quick chook-chooka-cha rhythm as distinctive as a Bo Diddley beat, and a sung or spoken “jingle” repeated and cut up into variations of increasing rhythmic complexity (called the sing-sing break or the think break).

Rod Lee, the revered master and one of the style’s originators, recently launched his own label, Club Kingz Records. His “ Let’s get HIGH ” track with K-Life, settles into a stroboscopic flicker on that single key word, “HIGH HIGH HIGH HIGH…” and feels like the summation of everything you’re on the dance floor to get.

Like the raw force of early rock, club is a propulsive, hilariously vulgar music for folks in need of release. “My music comes from anger,” Rod Lee told Stephen Janis in a recent interview in the local arts journal Link. “You got people going to the club to have a drink ’ cause they’re mad at their females. You got guys going to the club to get away from their bills … If you could sit there and make someone dance after they got divorced [laughter], I know I’m good!”

Non-club-going Baltimoreans have caught on to the sound listening to Friday night broadcasts on 92.3 FM. Some of the best DJs, including K-Swift, Frank Ski, and Cornbread are featured every week spinning at the most visible nightclub for the club sound, Club Choices on Charles Street. Rod Lee also has a regular Friday evening residency on the station.

Meanwhile, nationwide hipsters and tastemakers, like East Orange, New Jersey’s WFMU program director Brian Turner, have started ordering club tracks to add to their collections. While the original outlet for club, Music Liberated on West Saratoga, closed its doors after the death of proprietor Bernie Rabinowitz two years ago, and DJ Technic’s Club Tracks store just folded, Rod Lee plans to fill the gap this year with new shops on Monument Street and West Saratoga.

—Ian Nagoski

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Baltimore club music is the style which mr Swiss Beats is appropiating (aka biting) in order to make these new songs for cassidy ,T.I , Memphis Bleek, and Jae (Ness ate him) Millz. Its basically a looping style which use's Hip Hop phrases which would make good old uncle Luke blush. either way its party worthy and its not on MTV, so those in the know go give it a listen.

R J Noriega

what is happening to hip hop media

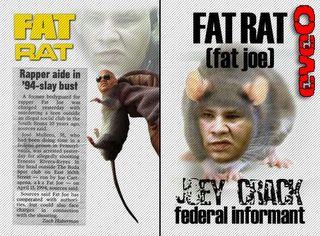

Why in the name of god is Fat Joe on the cover of XXL with a qoute about his street cred being equal with Tupac's? I mean from the video (and his new found flow) I thought he was trying to bite off of Jay and thus from biting association automatically be biting off of Big's style (so many Sharks in the game these days makes the whole thing seem murky.) Joe needs to make his mind up, either bite Tupac (like 50) or bite Jay (like fab, cassidy, and T.I) . And there is no reason on earth Eminem should be on the cover of SCRATCH (except if like all other parts of hip hop its after that britney money) . A producer/DJ magazine should be for people who excel at it, not moon light at it.

In fact he only made some wack beats that all sounded like "till i collapse". If they wanted a white guy Alchemist is 100 times better and I hear Scott Storch is willing to do whatever for publicity (like lil kim).

Oh the source and vibe are cock riders too (I was watching CB4 today and died every time the source reporter acted like she really wasn't a groupie with a pen lol.)

man it sad when hip-hop magazines end up becoming the equvalent of PEOPLE magazine for Negroes and Latinoes. but hey on a bright note Common is dropping a CD and he has shown before that he isnt scared of the music industry. Maybe he will stop doing prince wannabe albums and put people in their place again.

In fact he only made some wack beats that all sounded like "till i collapse". If they wanted a white guy Alchemist is 100 times better and I hear Scott Storch is willing to do whatever for publicity (like lil kim).

Oh the source and vibe are cock riders too (I was watching CB4 today and died every time the source reporter acted like she really wasn't a groupie with a pen lol.)

man it sad when hip-hop magazines end up becoming the equvalent of PEOPLE magazine for Negroes and Latinoes. but hey on a bright note Common is dropping a CD and he has shown before that he isnt scared of the music industry. Maybe he will stop doing prince wannabe albums and put people in their place again.

Thursday, March 24, 2005

REGGAETON!!!

Reggaeton is a relatively new genre of dance music that has become popular in Puerto Rico over the last decade. The name is derived from the reggae music of Jamaica which influenced reggaeton's dance beat. Reggaeton was also heavily influenced by other Puerto Rican music genres and by urban hip-hop music craze in the United States.

The variety of musical influences on the development of reggaeton led one observer (James Farber of the NY Daily News) to call it a "cultural polyglot".

As is the case with hip-hop music in the United States, reggaeton appeals primarily to youths. In Puerto Rico, youths were inspired to create reggaeton, after hearing Panamanian artists performing raps in Spanish styled after Jamaican dance-hall raps, adding native bomba and salsa, rhythms. The result can be heard in this example: Reggaeton Mix 1 by the Florida based band, BariMix.

Reggaeton is closely associated with the "underground" movement of urban youth and is sometimes also referred to in Spanish as "perro", meaning "doggie"; a term used to describe a common reggaeton dance move that evokes a sexual position.

The reggaeton genre has also become popular in other Caribbean islands and neighboring nations, including the Dominican Republic, Perú, Venezuela, Colombia, Mexico, Panama and Nicaragua. More recently, it has surfaced in the United States, particularly in those urban areas with large concentrations of Puerto Ricans or other Hispanics, such as New York and Miami.

The explosion in reggaeton's popularity in Latino urban centers have prompted some to speculate that the genre will soon eclipse salsa, merengue and other pop music among Puerto Rican and other Hispanic youth. In part, this might be due to lyrics on issues and subjects of interest to those audiences: urban crime, sex and racism; issues which have similarly made hip-hop music so popular.

Currently, the leading exponents of reggaeton include Tego Calderón, Queen Ivy, Don Chezina and Daddy Yankee, but the explosive growth in the genre's popularity promises to bring many new artists to the dance halls and discotheques and thereby, to the forefront of the urban youth culture.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

I love this music (well considering my housemate wakes me up with this stuff daily I had to learn to) . I have seen the same level of brand loyalty given to this music by Latina's as reggae gets from Jamaican women (For those not in the know that means they will sit down at a club/party whenever this isnt being played). To make things seem all the more like I went back to two years ago (when most of the best reggaeton songs first hit my ear) I hear this remix of "No Es Amor" which is like Aventura's biggest song ever. But now its sung by Frankie J (I wonder was he in Aventura) which while losing the original Bachata flavor is still a damn good love song. The only excuse I can come up with for all this good music being repackaged is that unlike last time the "Latin invasion" is being carried out by the darker hued Latinos

There are MC's.....There are Rappers... then there are cornballs who say stay together when you know you always got to say change of heart...even if you dont really mean it.

Wednesday, March 23, 2005

It's a Celebration Bitches!!!

Hiphop Turns 30Whatcha celebratin' for?

by Greg Tate January 4th, 2005

We are now winding down the anniversary of hiphop's 30th year of existence as a populist art form. Testimonials and televised tributes have been airing almost daily, thanks to Viacom and the like. As those digitized hiphop shout-outs get packed back into their binary folders, however, some among us have been so gauche as to ask, What the heck are we celebrating exactly? A right and proper question, that one is, mate. One to which my best answer has been: Nothing less, my man, than the marriage of heaven and hell, of New World African ingenuity and that trick of the devil known as global hyper-capitalism. Hooray.

Given that what we call hiphop is now inseparable from what we call the hiphop industry, in which the nouveau riche and the super-rich employers get richer, some say there's really nothing to celebrate about hiphop right now but the moneyshakers and the moneymakers—who got bank and who got more.

Hard to argue with that line of thinking since, hell, globally speaking, hiphop is money at this point, a valued form of currency where brothers are offered stock options in exchange for letting some corporate entity stand next to their fire.

True hiphop headz tend to get mad when you don't separate so-called hiphop culture from the commercial rap industry, but at this stage of the game that's like trying to separate the culture of urban basketball from the NBA, the pro game from the players it puts on the floor

Hiphop may have begun as a folk culture, defined by its isolation from mainstream society, but being that it was formed within the America that gave us the coon show, its folksiness was born to be bled once it began entertaining the same mainstream that had once excluded its originators. And have no doubt, before hiphop had a name it was a folk culture—literally visible in the way you see folk in Brooklyn and the South Bronx of the '80s, styling, wilding, and profiling in Jamel Shabazz's photograph book Back in the Days. But from the moment "Rapper's Delight" went platinum, hiphop the folk culture became hiphop the American entertainment-industry sideshow.

No doubt it transformed the entertainment industry, and all kinds of people's notions of entertainment, style, and politics in the process. So let's be real. If hiphop were only some static and rigid folk tradition preserved in amber, it would never have been such a site for radical change or corporate exploitation in the first place. This being America, where as my man A.J.'s basketball coach dad likes to say, "They don't pay niggas to sit on the bench," hiphop was never going to not go for the gold as more gold got laid out on the table for the goods that hiphop brought to the market. Problem today is that where hiphop was once a buyer's market in which we, the elite hiphop audience, decided what was street legit, it has now become a seller's market, in which what does or does not get sold as hiphop to the masses is whatever the boardroom approves.

The bitter trick is that hiphop, which may or may not include the NBA, is the face of Black America in the world today. It also still represents Black culture and Black creative license in unique ways to the global marketplace, no matter how commodified it becomes. No doubt, there's still more creative autonomy for Black artists and audiences in hiphop than in almost any other electronic mass-cultural medium we have. You for damn sure can't say that about radio, movies, or television. The fact that hiphop does connect so many Black folk worldwide, whatever one might think of the product, is what makes it invaluable to anyone coming from a Pan-African state of mind. Hiphop's ubiquity has created a common ground and a common vernacular for Black folk from 18 to 50 worldwide. This is why mainstream hiphop as a capitalist tool, as a market force isn't easily discounted: The dialogue it has already set in motion between Long Beach and Cape Town is a crucial one, whether Long Beach acknowledges it or not. What do we do with that information, that communication, that transatlantic mass-Black telepathic link? From the looks of things, we ain't about to do a goddamn thing other than send more CDs and T-shirts across the water.

But the Negro art form we call hiphop wouldn't even exist if African Americans of whatever socioeconomic caste weren't still niggers and not just the more benign, congenial "niggas." By which I mean if we weren't all understood by the people who run this purple-mountain loony bin as both subhuman and superhuman, as sexy beasts on the order of King Kong. Or as George Clinton once observed, without the humps there ain't no getting over. Meaning that only Africans could have survived slavery in America, been branded lazy bums, and decided to overcompensate by turning every sporting contest that matters into a glorified battle royal.

Like King Kong had his island, we had the Bronx in the '70s, out of which came the only significant artistic movement of the 20th century produced by born-and-bred New Yorkers, rather than Southwestern transients or Jersey transplants. It's equally significant that hiphop came out of New York at the time it did, because hiphop is Black America's Ellis Island. It's our Delancey Street and our Fulton Fish Market and garment district and Hollywoodian ethnic enclave/empowerment zone that has served as a foothold for the poorest among us to get a grip on the land of the prosperous.

Only because this convergence of ex-slaves and ch-ching finally happened in the '80s because hey, African Americans weren't allowed to function in the real economic and educational system of these United States like first-generation immigrants until the 1980s—roughly four centuries after they first got here, 'case you forgot. Hiphoppers weren't the first generation who ever thought of just doing the damn thang entreprenurially speaking, they were the first ones with legal remedies on the books when it came to getting a cut of the action. And the first generation for whom acquiring those legal remedies so they could just do the damn thang wasn't a priority requiring the energies of the race's best and brightest.

If we woke up tomorrow and there was no hiphop on the radio or on television, if there was no money in hiphop, then we could see what kind of culture it was, because my bet is that hiphop as we know it would cease to exist, except as nostalgia. It might resurrect itself as a people's protest music if we were lucky, might actually once again reflect a disenchantment with, rather than a reinforcement of, the have and have-not status quo we cherish like breast milk here in the land of the status-fiending. But I won't be holding my breath waiting to see.

Because the moment hiphop disappeared from the air and marketplace might be the moment when we'd discover whether hiphop truly was a cultural force or a manufacturing plant, a way of being or a way of selling porn DVDs, Crunk juice, and S. Carter signature sneakers, blessed be the retired.

That might also be the moment at which poor Black communities began contesting the reality of their surroundings, their life opportunities. An interesting question arises: If enough folk from the 'hood get rich, does that suffice for all the rest who will die tryin'? And where does hiphop wealth leave the question of race politics? And racial identity?

Picking up where Amiri Baraka and the Black Arts Movement left off, George Clinton realized that anything Black folk do could be abstracted and repackaged for capital gain. This has of late led to one mediocre comedy after another about Negroes frolicking at hair shows, funerals, family reunions, and backyard barbecues, but it has also given us Biz Markie and OutKast.

Oh, the selling power of the Black Vernacular. Ralph Ellison only hoped we'd translate it in such a way as to gain entry into the hallowed house of art. How could he know that Ralph Lauren and the House of Polo would one day pray to broker that vernacular's cool marketing prowess into a worldwide licensing deal for bedsheets writ large with Jay-Z's John Hancock? Or that the vernacular's seductive powers would drive Estée Lauder to propose a union with the House of P. Diddy? Or send Hewlett-Packard to come knocking under record exec Steve Stoute's shingle in search of a hiphop-legit cool marketer?

Oh, the selling power of the Black Vernacular. Ralph Ellison only hoped we'd translate it in such a way as to gain entry into the hallowed house of art. How could he know that Ralph Lauren and the House of Polo would one day pray to broker that vernacular's cool marketing prowess into a worldwide licensing deal for bedsheets writ large with Jay-Z's John Hancock? Or that the vernacular's seductive powers would drive Estée Lauder to propose a union with the House of P. Diddy? Or send Hewlett-Packard to come knocking under record exec Steve Stoute's shingle in search of a hiphop-legit cool marketer?

Hiphop's effervescent and novel place in the global economy is further proof of that good old Marxian axiom that under the abstracting powers of capitalism, "All that is solid melts into air" (or the Ethernet, as the case might be). So that hiphop floats through the virtual marketplace of branded icons as another consumable ghost, parasitically feeding off the host of the real world's people—urbanized and institutionalized—whom it will claim till its dying day to "represent." And since those people just might need nothing more from hiphop in their geopolitically circumscribed lives than the escapism, glamour, and voyeurism of hiphop, why would they ever chasten hiphop for not steady ringing the alarm about the African American community's AIDS crisis, or for romanticizing incarceration more than attacking the prison-industrial complex, or for throwing a lyrical bone at issues of intimacy or literacy or, heaven forbid, debt relief in Africa and the evils perpetuated by the World Bank and the IMF on the motherland?

All of which is not to say "Vote or Die" wasn't a wonderful attempt to at least bring the phantasm of Black politics into the 24-hour nonstop booty, blunts, and bling frame that now has the hiphop industry on lock. Or to devalue by any degree Russell Simmons's valiant efforts to educate, agitate, and organize around the Rockefeller drug-sentencing laws. Because at heart, hiphop remains a radical, revolutionary enterprise for no other reason than its rendering people of African descent anything but invisible, forgettable, and dismissible in the consensual hallucination-simulacrum twilight zone of digitized mass distractions we call our lives in the matrixized, conservative-Christianized, Goebbelsized-by-Fox 21st century. And because, for the first time in our lives, race was nowhere to be found as a campaign issue in presidential politics and because hiphop is the only place we can see large numbers of Black people being anything other than sitcom window dressing, it maintains the potential to break out of the box at the flip of the next lyrical genius who can articulate her people's suffering with the right doses of rhythm and noise to reach the bourgeois and still rock the boulevard.

Call me an unreconstructed Pan-African cultural nationalist, African-fer-the-Africans-at-home-and-abroad-type rock and roll nigga and I won't be mad at ya: I remember the Afrocentric dream of hiphop's becoming an agent of social change rather than elevating a few ex-drug dealers' bank accounts. Against my better judgment, I still count myself among that faithful. To the extent that hiphop was a part of the great Black cultural nationalist reawakening of the 1980s and early '90s, it was because there was also an anti-apartheid struggle and anti-crack struggle, and Minister Louis Farrakhan and Reverend Jesse Jackson were at the height of their rhetorical powers, recruitment ambitions, and media access, and a generation of Ivy League Black Public Intellectuals on both sides of the Atlantic had come to the fore to raise the philosophical stakes in African American debate, and speaking locally, there were protests organized around the police/White Citizens Council lynchings of Bumpurs, Griffiths, Hawkins, Diallo, Dorismond, etc. etc. etc. Point being that hiphop wasn't born in a vacuum but as part of a political dynamo that seems to have been largely dissipated by the time we arrived at the Million Man March, best described by one friend as the largest gathering in history of a people come to protest themselves, given its bizarre theme of atonement in the face of the goddamn White House.

The problem with a politics that theoretically stops thinking at the limit of civil rights reform and appeals to white guilt and Black consciousness was utterly revealed at that moment—a point underscored by the fact that the two most charged and memorable Black political events of the 1990s were the MMM and the hollow victory of the O.J. trial. Meaning, OK, a page had been turned in the book of African American economic and political life—clearly because we showed up in Washington en masse demanding absolutely nothing but atonement for our sins—and we did victory dances when a doofus ex-athlete turned Hertz spokesmodel bought his way out of lethal injection. Put another way, hiphop sucks because modern Black populist politics sucks. Ishmael Reed has a poem that goes: "I am outside of history . . . it looks hungry . . . I am inside of history it's hungrier than I thot." The problem with progressive Black political organizing isn't hiphop but that the No. 1 issue on the table needs to be poverty, and nobody knows how to make poverty sexy. Real poverty, that is, as opposed to studio-gangsta poverty, newly-inked-MC-with-a-story-to-sell poverty.

You could argue that we're past the days of needing a Black agenda. But only if you could argue that we're past the days of there being poor Black people and Driving While Black and structural, institutionalized poverty. And those who argue that we don't need leaders must mean Bush is their leader too, since there are no people on the face of this earth who aren't being led by some of their own to hell or high water. People who say that mean this: Who needs leadership when you've got 24-hour cable and PlayStations. And perhaps they're partly right, since what people can name and claim their own leaders when they don't have their own nation-state? And maybe in a virtual America like the one we inhabit today, the only Black culture that matters is the one that can be downloaded and perhaps needs only business leaders at that. Certainly it's easier to speak of hiphop hoop dreams than of structural racism and poverty, because for hiphop America to not just desire wealth but demand power with a capital P would require thinking way outside the idiot box.

Consider, if you will, this "as above, so below" doomsday scenario: Twenty years from now we'll be able to tell our grandchildren and great-grandchildren how we witnessed cultural genocide: the systematic destruction of a people's folkways.

We'll tell them how fools thought they were celebrating the 30th anniversary of hiphop the year Bush came back with a gangbang, when they were really presiding over a funeral. We'll tell them how once upon a time there was this marvelous art form where the Negro could finally say in public whatever was on his or her mind in rhyme and how the Negro hiphop artist, staring down minimum wage slavery, Iraq, or the freedom of the incarcerated chose to take his emancipated motor mouth and stuck it up a stripper's ass because it turned out there really was gold in them thar hills.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

While I agree with this article for the most part. The way it is worded somehow reminds me of something Delores Tucker would write. While this was written for the villiage voice (who are in some ways just far from hip hop as President Dubba) it did have its points about hip hop being a folk music that has been incorporated into the same machine which use to claim it came from a demon culture (see CB4, funny ass movie).

But at the same time it makes me wonder is Greg Tate a good example of what happens when old hip hop heads grow up and join the middle class and decide that the music got a little too loud (or should I say Crunk) for them. His opinion on the million man march and OJ are his own so I wont critque them and his use of stats to support his argument "that we are paying attention to the wrong thing" seem mute too me. If he truly cared about these things he should of wrote a report about them. Or better yet questioned why the government cant foot the bill to improve health care while we send our communities young to fight for their right to sell oil outside of OPEC influences. But maybe the critque of whats really wrong is too scary for people to really try

Beat a retreat? While Kanye West looks within and Mos Def styles himself as a quasi-jihadist, a head wonders, what happened to the rage, urgency, and political direction in hip-hop?

By Oliver Wang

For all the social rancor of recent times – especially during the election year just past – hip-hop artists have been conspicuously quiet. The funeral dirge for rap music's social irrelevance has played for more than a decade now, but it was far easier to understand hip-hop's political indifference during the complacency of the Clinton era. In a 2003 interview with the Believer, Roots drummer Ahmir Thompson argued that as devastating as the 1980s crack wars were for black communities, they also spurred rappers to confront those dire times in inspired and creative ways. Said Thompson, "Reagan and Bush gave us the best years of hip-hop."

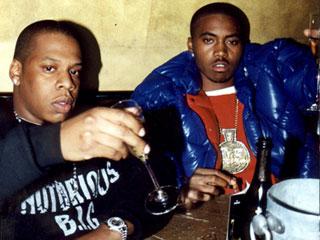

In comparison, the '90s led rappers into irrational exuberance, and the anthem changed from Public Enemy's "Brothers Gonna Work It Out" to Jay-Z's "Big Pimpin'." Believe it or not, this isn't an impassioned, nostalgic cry for hip-hop to take it back to '88. Kente cloth and Africa medallions had their time and place, just like acid-wash jeans and high-top fades – I'm not complaining that hip-hop's political styles were retired, but what happened to the rage? Rap music's social silence has never screamed more loudly than now, in the midst of the most divisive presidency in decades, the prospect of war without end, and a fundamentalist movement trying to take society back to '88 – 1888.

I've been pondering why outrage escaped from hip-hop, and I always flash back to the Los Angeles uprising of 1991. Rappers like Ice Cube and Ice-T had prophesied the coming conflagration for years before, but once L.A. actually blew up into flames and everyone's passions were spent, reviving that fury seemed moot. It's not a coincidence that Ice Cube's career began its downward slide after '91 or that Dr. Dre and Snoop scored with The Chronic (Death Row, 1992) by trading in righteous anger for gangsta cool. Back east, Afrocentric idealism paled next to the gritty realism of crack war diaries from the likes of Mobb Deep and Biggie. It's hard to tell whether socially engaged hip-hop abandoned the market or vice versa, but by 1997, Puff Daddy's No Way Out (Bad Boy) became an ironically apt description for the direction in which hip-hop seemed permanently headed.

This isn't to say the entire rap community has collectively shrugged its shoulders. Two of the biggest political anthems made last year came from unlikely sources: Jadakiss and Eminem. Jada's "Why?" became one of the summer's biggest hits, asking a series of pointed questions such as "Why'd they let the Terminator win the election?" and "Why'd the president knock down the towers?," which MTV censored out. Meanwhile, Eminem's "Mosh" was a surprising call to organize youth off the streets and into voting booths.

No one expected Jadakiss and Em to stand in as hip-hop's political firebrands, especially since the two who previously filled those roles – Talib Kweli and Mos Def – are still around. However, Mos and Talib had little to say of any real consequence on their respective albums from '04, The New Danger (Geffen) and The Beautiful Struggle (Rawkus). Neither artist should be obligated to be a community spokesperson, but after positioning themselves as hip-hop's moral center in the late 1990s with their Black Star collaboration, it's surprising their new albums are so apolitical, especially in such a tense year. Mos's album image of himself, dressed up quasi-jihadist, makes a strong statement about the racial politics of the war on terror, but unfortunately, none of the songs on either his or Talib's LP could match that poignancy.

The waning of Black Star is indicative of how hip-hop's so-called consciousness is in a state of crisis, and ironically, that's partially come about from rap's current self-consciousness. The resounding success of Kanye West's College Dropout (Roc-A-Fella) is instructive here – when West brags he's the "first nigga with a Benz and a backpack," he's transforming the terms of conscious rap. Songs like "All Falls Down" and "Jesus Walks" reflect a redirection of mental energy inward as West interrogates himself and probes his own weaknesses. On "Breathe In, Breathe Out," he essentially admits, "Yes, I rock ice, but I feel bad about it," and his honesty is meant as absolution.

This is hardly new. Jay-Z and Eminem built entire careers on calculated apologies – West just improves on them, seamlessly marrying the Protestant work ethic and the hustler's credo. If West's doing well, that's proof that Jesus walks – with him. Armed with divine approval, West masterfully proselytizes by blending subtle class politics, personal improvement rhetoric, and undeniably compelling music. A song like "Spaceship," which finds West fantasizing about escaping the doldrums of dead-end retail work, speaks to the frustrations of many youths facing a lifetime of being nickel-and-dimed to death.

The new rap introspection has its charms, but it often means shunting aside the outside world. West's politics are mostly personal, offering a vision for individual uplift – Horatio Alger as a hustler – but he has far less to say about the world around him than his predecessors did. One notable exception by a commercial artist is Nas's new, sprawling Street's Disciple (Sony), which sternly takes political and public icons to task. Nas busts out a blacklist of African American sellouts on a pair of songs: "American Way" and "These Are Our Heroes." Condi Rice and Kobe Bryant rank high on his list of "coon Uncle Tom fools." The rapper's self-righteousness can be hard to swallow – he hasn't always been NAACP Image Award material either – but it's invigorating to hear such a prominent artist invite controversy and take a stand on something besides his own frailties.

Not surprisingly, if a new model is being drafted, the underground is supplying part of the blueprint. Artists like Immortal Technique and Dead Prez offered some of the loudest protest anthems in 2004, and in 2005 the Perceptionists – a new collabo between part-time Bay Arean Mr. Lif and Boston's Akrobatik and Faqts One – promise to keep ringing the alarm.

There's no elliptical metaphors or hidden transcripts to decipher: the Perceptionists aim directly at the source. On "Memorial Day," they ask, "Where are the weapons of mass destruction? / We been looking for months and we ain't found nothin' / Please Mr. President / Tell us something / We knew from the beginning that your ass was bluffing." Their topicality is scalpel-sharp, indicting Donald Rumsfeld's incompetent war-making and standing up for working-class soldiers, and all set over a beat barrage of chaotic strings and drum explosions. Though their upcoming March album, Black Dialogue, has its moments of levity – they team with Oakland's Humpty Hump for the hilarious "Career Finders" – their project is clearly driven by an incisive, political urgency, and it's one of the few recordings that feed into and out of our current tensions. The Perceptionists confront hip-hop's line in the sand – with smug complacency on one side and political peril on the other – and they choose to charge across. Do we dare follow?

-------------------------------------------------------------------

The best way to answer this above report about Hip Hop losing its fire brand is too say thats its time we go about an break hip hop down officially. The foolish notion that depending on which region (east/west/south/mid west) of america you live in decides how you will make music must end. Just like Reggae which has its feet in Lover's rock , and Roots and Culture (Capleton post shiloh), and Dancehall (Sean Paul and Elephant Man) Yes its all reggae but its separated in the store.

But more than a better categorizing system the culture as a whole needs leaders. But its a harder task said than done. Cultural leaders like rappers are the influential choice makers, while elected leaders take a back seat. Yet most elected leaders never came from the same situation as most colored people and thus can only relate so much to our daily struggles. So here is the root of the problem. the upper class and lower class blacks and Latinos are so separated by Cash we cant see eye to eye on the important things. Where is the NAACP and why does Sharpton speak up when shit happens alone.

If people really want to realize the problem of why we cant connect as a people to better all our lives people need to learn about the Scottsboro Boys and response of those who are suppose to lead us. Talented Tenth my ass!!! I say look to the Jews and how they went about the last hundered years and you will learn the answer.

And what is the answer. The answer is stop shitting on each other cause we are all in the same boat crossing the atlantic. Until we figure out that money doesnt make people better than they were before they had it we are gonna stay stuck in the mud and never find our own version of Zion!!

By Oliver Wang

For all the social rancor of recent times – especially during the election year just past – hip-hop artists have been conspicuously quiet. The funeral dirge for rap music's social irrelevance has played for more than a decade now, but it was far easier to understand hip-hop's political indifference during the complacency of the Clinton era. In a 2003 interview with the Believer, Roots drummer Ahmir Thompson argued that as devastating as the 1980s crack wars were for black communities, they also spurred rappers to confront those dire times in inspired and creative ways. Said Thompson, "Reagan and Bush gave us the best years of hip-hop."

In comparison, the '90s led rappers into irrational exuberance, and the anthem changed from Public Enemy's "Brothers Gonna Work It Out" to Jay-Z's "Big Pimpin'." Believe it or not, this isn't an impassioned, nostalgic cry for hip-hop to take it back to '88. Kente cloth and Africa medallions had their time and place, just like acid-wash jeans and high-top fades – I'm not complaining that hip-hop's political styles were retired, but what happened to the rage? Rap music's social silence has never screamed more loudly than now, in the midst of the most divisive presidency in decades, the prospect of war without end, and a fundamentalist movement trying to take society back to '88 – 1888.

I've been pondering why outrage escaped from hip-hop, and I always flash back to the Los Angeles uprising of 1991. Rappers like Ice Cube and Ice-T had prophesied the coming conflagration for years before, but once L.A. actually blew up into flames and everyone's passions were spent, reviving that fury seemed moot. It's not a coincidence that Ice Cube's career began its downward slide after '91 or that Dr. Dre and Snoop scored with The Chronic (Death Row, 1992) by trading in righteous anger for gangsta cool. Back east, Afrocentric idealism paled next to the gritty realism of crack war diaries from the likes of Mobb Deep and Biggie. It's hard to tell whether socially engaged hip-hop abandoned the market or vice versa, but by 1997, Puff Daddy's No Way Out (Bad Boy) became an ironically apt description for the direction in which hip-hop seemed permanently headed.

This isn't to say the entire rap community has collectively shrugged its shoulders. Two of the biggest political anthems made last year came from unlikely sources: Jadakiss and Eminem. Jada's "Why?" became one of the summer's biggest hits, asking a series of pointed questions such as "Why'd they let the Terminator win the election?" and "Why'd the president knock down the towers?," which MTV censored out. Meanwhile, Eminem's "Mosh" was a surprising call to organize youth off the streets and into voting booths.

No one expected Jadakiss and Em to stand in as hip-hop's political firebrands, especially since the two who previously filled those roles – Talib Kweli and Mos Def – are still around. However, Mos and Talib had little to say of any real consequence on their respective albums from '04, The New Danger (Geffen) and The Beautiful Struggle (Rawkus). Neither artist should be obligated to be a community spokesperson, but after positioning themselves as hip-hop's moral center in the late 1990s with their Black Star collaboration, it's surprising their new albums are so apolitical, especially in such a tense year. Mos's album image of himself, dressed up quasi-jihadist, makes a strong statement about the racial politics of the war on terror, but unfortunately, none of the songs on either his or Talib's LP could match that poignancy.

The waning of Black Star is indicative of how hip-hop's so-called consciousness is in a state of crisis, and ironically, that's partially come about from rap's current self-consciousness. The resounding success of Kanye West's College Dropout (Roc-A-Fella) is instructive here – when West brags he's the "first nigga with a Benz and a backpack," he's transforming the terms of conscious rap. Songs like "All Falls Down" and "Jesus Walks" reflect a redirection of mental energy inward as West interrogates himself and probes his own weaknesses. On "Breathe In, Breathe Out," he essentially admits, "Yes, I rock ice, but I feel bad about it," and his honesty is meant as absolution.

This is hardly new. Jay-Z and Eminem built entire careers on calculated apologies – West just improves on them, seamlessly marrying the Protestant work ethic and the hustler's credo. If West's doing well, that's proof that Jesus walks – with him. Armed with divine approval, West masterfully proselytizes by blending subtle class politics, personal improvement rhetoric, and undeniably compelling music. A song like "Spaceship," which finds West fantasizing about escaping the doldrums of dead-end retail work, speaks to the frustrations of many youths facing a lifetime of being nickel-and-dimed to death.

The new rap introspection has its charms, but it often means shunting aside the outside world. West's politics are mostly personal, offering a vision for individual uplift – Horatio Alger as a hustler – but he has far less to say about the world around him than his predecessors did. One notable exception by a commercial artist is Nas's new, sprawling Street's Disciple (Sony), which sternly takes political and public icons to task. Nas busts out a blacklist of African American sellouts on a pair of songs: "American Way" and "These Are Our Heroes." Condi Rice and Kobe Bryant rank high on his list of "coon Uncle Tom fools." The rapper's self-righteousness can be hard to swallow – he hasn't always been NAACP Image Award material either – but it's invigorating to hear such a prominent artist invite controversy and take a stand on something besides his own frailties.

Not surprisingly, if a new model is being drafted, the underground is supplying part of the blueprint. Artists like Immortal Technique and Dead Prez offered some of the loudest protest anthems in 2004, and in 2005 the Perceptionists – a new collabo between part-time Bay Arean Mr. Lif and Boston's Akrobatik and Faqts One – promise to keep ringing the alarm.

There's no elliptical metaphors or hidden transcripts to decipher: the Perceptionists aim directly at the source. On "Memorial Day," they ask, "Where are the weapons of mass destruction? / We been looking for months and we ain't found nothin' / Please Mr. President / Tell us something / We knew from the beginning that your ass was bluffing." Their topicality is scalpel-sharp, indicting Donald Rumsfeld's incompetent war-making and standing up for working-class soldiers, and all set over a beat barrage of chaotic strings and drum explosions. Though their upcoming March album, Black Dialogue, has its moments of levity – they team with Oakland's Humpty Hump for the hilarious "Career Finders" – their project is clearly driven by an incisive, political urgency, and it's one of the few recordings that feed into and out of our current tensions. The Perceptionists confront hip-hop's line in the sand – with smug complacency on one side and political peril on the other – and they choose to charge across. Do we dare follow?

-------------------------------------------------------------------

The best way to answer this above report about Hip Hop losing its fire brand is too say thats its time we go about an break hip hop down officially. The foolish notion that depending on which region (east/west/south/mid west) of america you live in decides how you will make music must end. Just like Reggae which has its feet in Lover's rock , and Roots and Culture (Capleton post shiloh), and Dancehall (Sean Paul and Elephant Man) Yes its all reggae but its separated in the store.

But more than a better categorizing system the culture as a whole needs leaders. But its a harder task said than done. Cultural leaders like rappers are the influential choice makers, while elected leaders take a back seat. Yet most elected leaders never came from the same situation as most colored people and thus can only relate so much to our daily struggles. So here is the root of the problem. the upper class and lower class blacks and Latinos are so separated by Cash we cant see eye to eye on the important things. Where is the NAACP and why does Sharpton speak up when shit happens alone.

If people really want to realize the problem of why we cant connect as a people to better all our lives people need to learn about the Scottsboro Boys and response of those who are suppose to lead us. Talented Tenth my ass!!! I say look to the Jews and how they went about the last hundered years and you will learn the answer.

And what is the answer. The answer is stop shitting on each other cause we are all in the same boat crossing the atlantic. Until we figure out that money doesnt make people better than they were before they had it we are gonna stay stuck in the mud and never find our own version of Zion!!